The Dignity of Risk

- Oct 21, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2023

This time of year naturally brings memories of Gay’s transition from our world to a new place, reflections on change with the fall leaves dropping from the trees, and thoughts of the year ahead.

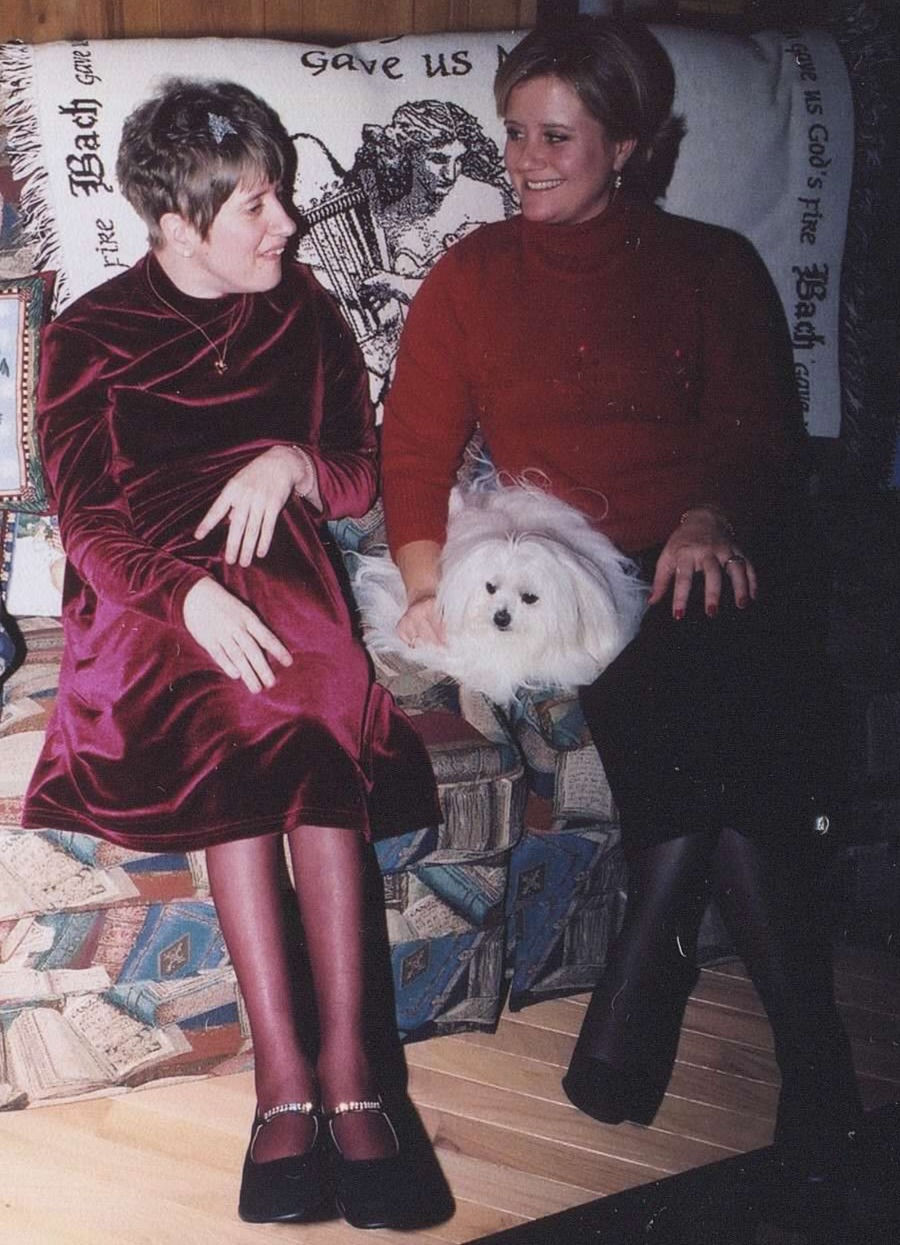

Although it’s been almost a year since I last blogged, Gay continues to be on my mind through little things I do every day (like eating pears with cinnamon) and more complex reflections on how I want to be and live in the world without her physical presence in it. I love this picture because I will always remember the brightness of her smile.

This year I’ve made some definitive choices about the future and have been learning a lot about what it means to live on my own after interacting with a household full of people for over 4 years. Spending time with my closest friends has been centering and comforting. I also found and lost love as I ventured into what I hoped would be a lifetime partnership. Spending time with my parents about once a week is something I treasure, and I love having them close by should they need anything from me. I am making choices about my career, focusing less on title, advancement, or being recognized for accomplishments. I want the few years I have before retirement (or moving to part time work) to focus on supporting my colleagues as we ensure that all students can achieve their dreams, navigate college successfully, learn what they came to learn (and things they didn’t plan on learning) and make sure there are beneficial and equitable returns for the fiscal and human investment students entrust to the university.

And I’ve been thoughtfully considering my purpose for continuing to write about Gay and her influence on my life, our families’ and friends’ lives, and her community. Over the past month, I have identified four reasons for continuing to write:

1. Write Gay’s story and along with it bring to light the history of ability science, culture, and politics in the U.S.

2. Share a story of two sisters’ love and commitment to each other while challenging definitions of “normalcy” by paralleling our lives, strengths, accomplishments.

3. Honor the ways that our parents nurtured our growth and perseverance by taking risks, allowing us to take risks, and challenging societal expectations of what we could or “should” do/behave etc. while also adhering to a duty of care for someone whose voice was not always acknowledged or heard by others.

4. Affirm the value of all people’s lives – especially those with abilities that are not always seen or recognized by our society.

I am sure these ideas will continue to shift and change as I continue to write but I think they capture the main ideas and are the building blocks for whatever comes next. For this blog, there are two cornerstone concepts that I want to introduce to our readers/followers: 1) dignity of risk and 2) duty of care. These are concepts like “support” and “challenge” in higher education (Sanford, 1967; Evans et.al. 20009) or “in loco parentis” but they take on different meaning when connected with disability rights.

My parents often talked about how when they had to make tough choices to intervene for Gay (duty of care) or promote her independence, Dr. Barr, Gay’s doctor for many years, would talk with them about “dignity of risk” (a concept introduced by Robert Perske in 1972). From what I have learned, many of these decisions came up around Gay’s educational environments or living arrangements including her short stay in a group home in Monroe, and her move into an apartment of her own in Manistique, Michigan in 1999/2000. Although the group home arrangement provided a higher sense of security in some ways because it was staffed 24/7, it didn’t work well. Other residents were too noisy for Gay, and she couldn’t express herself in ways that allowed her desires and choices to be considered (leading to concerns about her physical and emotional safety). The behavioral approach used in the home frustrated Gay, and because she had trouble adapting to the structure, it meant she was deprived of outings and other things she enjoyed. The apartment arrangement was not staffed 24/7 because Gay was monitored by a camera and an alarm once she went to bed at night (if alarms went off, the small-town police and fire personnel were close and available). Although in some ways, that made Gay vulnerable by being alone at night, it also allowed her the dignity of privacy and choice about having people around her who could translate her needs for others.

And my parents applied these same principles of care and risk to me as I advanced my academic goals. They supported me driving myself to a high school over 30 minutes away in other state and my attendance at a large, Big 10, residential university. In both those situations, I have come to appreciate that my parents trusted me, believed in me, and found the balance between being present, available, and engaged while allowing me to dream. While my parents had their own fears and concerns, swinging the pendulum between risk and care too far at times, in totality they balanced the two well. This love, trust, and commitment promoted their daughters’ growth and the ability to persevere.

And that is story I hope to tell in the months and years ahead. Persevering as Differently Abled Sisters: Balancing Dignity of Risk and Duty of Care. I’ll start with our early childhood experiences in the next blog. Happy Fall, everyone!

Citations:

Sanford, N. (1967). EDUCATION FOR INDIVIDUAL DEVELOPMENT. NEW DIMENSIONS IN HIGHER EDUCATION, NUMBER 31.

Evans, N. J., Forney, D. S., Guido, F. M., Patton, L. D., & Renn, K. A. (2009). Student development in college: Theory, research, and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Comments